Conversations in Climate Change: Laudato Si’ One Year Later

It’s hard to believe it’s been a year since Pope Francis released Laudato Si’, an encyclical on climate change and caring for our common home. Every day we see how the changing environment is affecting our poorest brothers and sisters, and know we must do more.

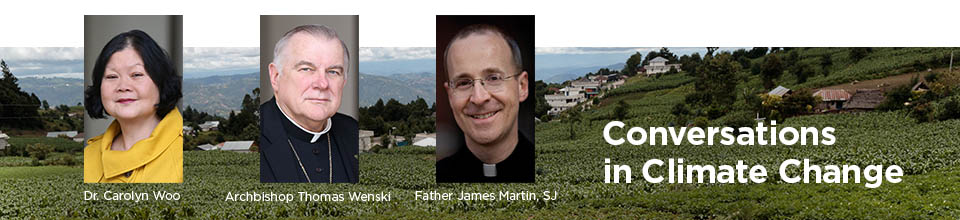

We recently sat down with Catholic Relief Services CEO Dr. Carolyn Woo, Miami Archbishop Thomas Wenski and Father James Martin, SJ of America Magazine to have a conversation about climate change and the legacy of Laudato Si’.

What impact have you observed the encyclical having in the last year?

Dr. Carolyn Woo: Clearly Americans, as well as Catholics in particular, have been affected by this encyclical. And, in fact, both groups are now more worried about climate change. They think it’s more real, that climate change is going to happen. Most encouraging is now more people—Catholics and Americans—think of this as an issue that affects the poor, and affects the next generations. So these are some of the changes I have seen.

Archbishop Thomas Wenski: I think perhaps the most important thing has been that Laudato Si’ saved [the] Paris [climate accord]. The meeting in Paris on the environment would not have made the progress it made without the support of Pope Francis and Laudato Si’. So I think Laudato Si’ has helped raise consciousness around the world. It saved Paris. And, in a lot of ways too, as Carolyn was saying, it helped open the eyes of our Catholics.

CRS: A follow-up question for you, Archbishop Wenski. You are in Miami, and climate change is an issue that’s really affecting people there now. What’s been the impact regionally in your part of the world?

Wenski: Let me preface this by saying that Laudato Si’ got me on the Stephen Colbert show. I was on the show when Pope Francis was celebrating Mass in Madison Square Garden.

He wanted to know about the impact of climate change in South Florida, especially Miami Beach where we suffer periodically from flooding and what are called "king tides." These tides flood the streets, and the city of Miami Beach has been investing perhaps a half a billion dollars in pumps to keep the streets dry during these tides. And so this is something that’s very real here in South Florida.

About 80 percent of that population of Florida lives along the coast. So we have a couple of thousand miles of coastline and sea level rising, which is a result of climate change.

“Climate change is not only a future threat, but also a present reality.” — Archbishop Thomas Wenski

CRS: And from one Colbert Show correspondent to another, Father Martin, what has been the impact you’ve seen this encyclical having over the last year?

Father James Martin, SJ: First of all, it created a great deal of discussion. And that was one of the Pope’s stated intentions in the document. [We have to] open it up for discussion. He says he’s not proposing any specific solutions, but it was an invitation for dialogue. And it certainly did that. I think it shocked people when it came out because obviously this is the first encyclical that has dealt with this in such a systematic way. And so it really jump-started the conversation.

Second, I think it forced Catholics to take a look at it as an issue. If you are a Catholic you can no longer say this is not something that [impinges] on me. An encyclical has a very high level of teaching authority, and a Catholic can’t simply dismiss it any longer as much as he or she would like. So, it brings it to the forefront of their consciousness.

Third, I think it really made the environmental community very grateful for the contribution of the Church. So often—I think unfortunately—the scientific community thinks that the Church is an adversary. And here is a situation where the Church is their ally, which I thought was fantastic. So overall, I think it really got people talking about the issues and when people dived into the encyclical, I think most of them were surprised at how comprehensive it was, and how thoughtful it was. It was a carefully worded, carefully argued document that people were forced to take seriously. So I think these things are really great results.

What part or parts of the encyclical have resonated with you personally in the last year?

Woo: Actually, I’d start with the title, Laudato Si’ or “Praised Be.” I thought that was ingenious as a title because immediately it points your attention to God, number one: God’s creation, praise be to God. The second thing is it raises a question mark: Is the way that we’re living really praise?

Wenski: It’s comprehensiveness and the fact that he talks about an integral ecology. There’s a natural ecology and there’s a human ecology, and it’s all based on relationships. In Laudato Si’, Pope Francis is saying that we have to get our relationships right. And if our relationship with God is off, if our relationship with our fellow human beings is off, then it’s hard to say that our relationship with nature won’t be [off]. All three of these relationships have to be harmonized.

The Pope is saying it is about transcendence. It’s about relationships with God, and that relationship has to be right if we’re going to get the relationship with our [fellow] human beings right and if we’re going to get our relationship with our common home correct as well.

Martin: Well, I would say two things. In general, reading it had a very strong impact on me. It’s hard to read that entire encyclical and not feel that it makes a claim on you, and not be forced to look at the way you live, and look at the way you live with one another, and at the way you advocate for change. I think that, as a Catholic, it simply brought it into my consciousness in a very strong way, in a way that frankly I hadn’t been thinking of.

A particular part that really resonated with me was a section called “The Gaze of Jesus.” His insight is not only that Jesus was part of creation and used creation—but that he enjoyed creation. And I frankly had never thought about that before. That Jesus, in first century Palestine, would have looked out at the Sea of Galilee, and flowers and wheat and clouds and birds, and would have enjoyed them. And that he, as a person who loves creation, and loved the things that the Father had made, would have appreciated them and found them beautiful.

That was very powerful for me in helping reframe our own gaze on creation. The things that Jesus looked at and loved, and were beautiful, are the things that we can look at and love and are beautiful.

Often when I preach sometimes, I say to people, imagine if they were in Palestine, a tree that we could be sure that Jesus used to look at and lean up against and pray next to and appreciate—maybe a tree that Jesus had planted—we would never do anything to that tree. We would love that tree. We would admire it and look at it, and people would come from all over the place. We would never, ever, ever cut it down. And this is what Francis is saying about all of creation in Jesus’ eyes. That creation is something that Jesus loved and enjoyed, and so therefore we should [revere] all of creation. So that was a really helpful insight for me and it really cast the climate change discussion in a much deeper and more profound light for me, just that one paragraph.

Why was it so important for this encyclical to be released?

Woo: Well, as Archbishop Wenski talked about, the Paris accord was coming on, and then there was also the UN Sustainable Development Goals which dealt with poverty, environment and rights, and so on. I think that Pope Francis was very strategic in releasing the encyclical at that point.

And overall we are in a period of great urgency. We cannot afford to waste any more time in terms of examining the type of actions and the type of policies that can move us to a low carbon economy and a low carbon environment. So I think the urgency, and particularly the specifics of the two major agreements, made it a really important time for the Pope to release this encyclical.

Wenski: It’s the first encyclical to deal directly with the environment, but also, it’s one of great continuity because it continues on the magisterium of St. John Paul II and also Benedict XVI. And I think, Benedict XVI was known by the press when he was pope as “The Green Pope." He, I believe, planted trees in a forest to offset the carbon imprint of the Vatican. He had solar panels put on the top of the audience hall. This encyclical makes Francis “The Greener Pope,” I guess, and it also shows what is sometimes called a natural development in the Church’s teachings on how social teachings develop and gather strength because of being built on past [statements] and past teachings of the [predecessors].

So John Paul II, Benedict XVI did not shy away from this issue, but they did not--at that point it was not [ripe] enough perhaps for an encyclical. And Francis’ time, it was the right time, and Francis seized the moment. And again, as I said earlier, it saved Paris. And had it not come out when it did, I don’t think Paris would’ve been the success that it was.

Martin: It gave the discussion on climate change a spiritual underpinning. Before Laudato Si’, the worldwide discussion was framed mainly in scientific, economic or moral terms. And while all of those were and are important, it did not have the systematic and comprehensive spiritual, sort of underpinning that Laudato Si’ provides. And so it provides a dimension that had been missing from the discussion and therefore makes the discussion much fuller, much more understandable for people, and much more compelling.

The encyclical emphasizes the power of climate change on the poor. What does Laudato Si’ mean for the people who CRS serves?

CRS: So let’s reverse it now. Father Martin to you.

Martin: Well, I was gonna laugh. I was gonna say, “Now that’s a question Carolyn should answer.”

[Laughter]

CRS: You want to tee it up for her?

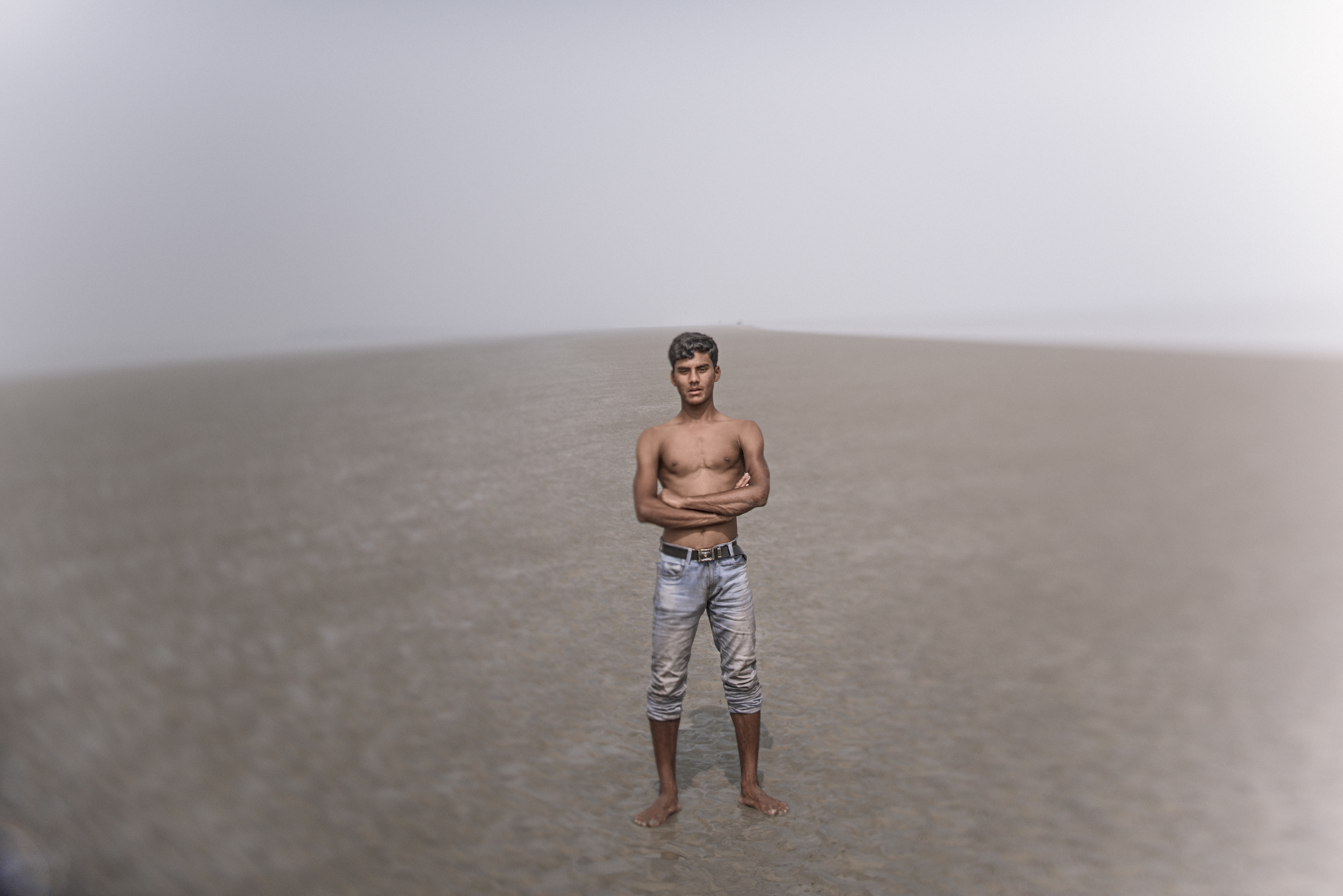

Martin: CRS serves exactly those people who Laudato Si’ is talking about. Those are the people on the margins. Those are the people that are most affected by climate change. And as the Pope says, one of the reasons that they are most affected by climate change is because they have fewer abilities to deal with it. If you're living in Bangladesh by the sea, you can’t move because you don’t have any money.

And you don’t have the wherewithal to defend yourself against climate change. So who are those people, where are they and what are they doing and what do they need? Well, they’re exactly the people that CRS serves. So what Laudato Si’ means for those people is a focus on their needs in a way that I don’t think has been done before by the Church.

“The Church has always looked out for the poor. And Jesus, of course, asked us in the Gospels to care for the poor above all other people. But the linkage between caring for the environment and caring for the poor has never been made so strongly.” — Father James Martin, SJ

So in a sense it affirms, in a different way, the wonderful work that CRS does all over the globe. So, it could be called “CRS’s Encyclical.”

Wenski: The poor are the ones who have had or are least responsible for the degradation of the environment, and they’re going to be the ones that will have to pay for its consequences, whether nothing is done or whether something is done. Oftentimes, the poor definitely don’t have the resources to move away from an area that’s impacted by, for example, the rising of tides. And if measures are taken that increase taxes in order to deal with climate change, the poor will end up paying a [disproportionate] share for the remedies unless some mitigation is taken to defray the burden that the poor might be asked to carry.

So I do think the encyclical does put the poor front and center, and reminds us that they suffer the consequences of climate change. It also challenges us that as we address climate change, we don’t make the poor suffer again.

Woo: I’m going to make four points. The first one is that, as I alluded earlier on, there are three billion people who will suffer the effects of climate change. And “suffer” is the word. And they’re the ones who are least responsible for creating this issue because they are too poor to really have the types of habits or industry that would lead to climate change. So for most people, and Catholics in particular, I think that the Pope raises this and it becomes a social justice issue. And we also know this has implications because down the road these countries will need resources in order to address this problem.

The second one I think is brilliant, is how the Pope links our way of living to the poor. And I think in fairly colorful strokes it illustrates the waste that we have, the consumption that we are addicted to, the selfishness in our society and how these different behaviors lead to other people suffering.

“He does such a beautiful job linking us to the very poor by...the lack of thoughtful and disciplined living.” — Dr. Carolyn Woo

The third point is of course we are seeing the effects of these consequences in the people we serve. We are addressing this problem from two dimensions. The first part, which is my point three, is about mitigation. And so CRS is very active working with Congress. We’ve visited quite a number of our representatives and our senators on this particular issue, asking what they’re doing.

But this is mitigation. We have to reduce the effect of carbon—reduce carbon in our economy. And so this whole area of mitigation, our website has this page specifically to illustrate these stories, educate our constituents so that they could actually see some of this, and again use their vote, use their voice to bring about a low carbon economy.

The fourth thing is really adaptation, and it is very sad to watch, because in Central America for example—and it’s not limited to just that region of the world, it’s actually around many different regions—but if you look at Central America agriculture, some of the productivity now of the crops are maybe one out of six of what it used to be.

Farmer Hugo Tzoy Pu lost his entire crop due to late rains in Guetamala. Photo by Phil Laubner/CRS.

Farmers used to be able to count on two rain seasons—a short one and a long one. The short one has gone away, and the long one is completely unpredictable. It’s not that there is no rain, it’s just that it doesn’t come at the time when you have planted your seeds, or when it comes it’s a deluge that it washes away the seeds rather than nurtures them.

And so we are seeing Central American farmers really suffering the effects and it renders them so poor. I mean, they were poor to start out with, but here they lose all the other assets and sometimes they have to sell their land. And when they sell their land they become homeless. They go and join the urban poor. We see this whole cycle of what climate change is doing and we’re trying to help people adapt by introducing different methods—perhaps different seed, planting different crops, moving from coffee, for example, to chocolate.

So we are going as fast as we know and adopting a lot of innovations along the way to help farmers adapt. Even one or two degree changes could affect them dramatically.

So my point really is, the whole area of mitigation and adaptation are the focuses of CRS work now, but thank the Pope for raising this as a social justice issue because it really is, and also linking us and our behavior to this problem.

What do you think the legacy will be for Laudato Si’?

Martin: Well, I think two things. First, it brings climate change into the Church’s rich tradition of social teaching. Interestingly, at the very beginning of the document, he says something like, “With this document I now add this to the body of Catholic social teaching.” So it’s very clear how he perceives the document.

It also brings the Church into the discussion—the worldwide discussion. And so the Church is now [part and partial] of the larger discussion.

“You really can’t talk about climate change without talking about Pope Francis and the encyclical. So it brings climate change into the Church, and Church into climate change, which I think is a wonderful legacy for the encyclical.” — Father James Martin, SJ

Wenski: I think the legacy is also a challenge to all of us to do what we can. And so the Pope cites the value of small efforts, of turning off light switches for example, or looking at our own patterns of consumption and looking to see what we can change for a more simple lifestyle.

In this sense, Laudato Si’ is telling us that each person can be part of the solution and that we’re challenged to rise to that challenge, to that task of being part of the solution. And we don’t have to be great scientists, we don’t have to be politicians who enact very complex policies. We can do our own share in our own neighborhood, in our own homes, and in our own parishes.

I know, for example, in the Archdiocese of Miami, my building apartment is working with parishes as they remodel and update things to make sure that they do what is the greenest option. In fact, one of my newest churches built, dedicated this past December, is LEED certified. Even the construction debris was recycled.

So all of us can do something, and all of us can make a difference no matter how small that something might be.

Woo: Anticipating some of the comments from Father Jim and Archbishop Wenski, I’m going to put my highlighter on a separate topic. And that is the science of climate change. Clearly, the encyclical said this is not a scientific document, but what it does is that it allows decades of climate science and other research which has been done to move into the mainstream.

There are a lot of people who reject climate science and said this is just manipulated. And the fact that the Pope says, “If you want to hear the cry of the poor, let science talk to you.” And I think it is important to address this issue: understanding the science of what causes climate change and how warm are we now and what are the consequences, and whether you can see it in the data. And I think that he allowed—he legitimizes I think—the decades and the huge body of scientific work which has been done on climate change.

Final comments?

Martin: I would say that ultimately the document is a document about conversion and it’s an invitation to conversion for everyone. It’s not something that he’s using to hit people over the head. It’s not something he’s using to [scold] people. It’s not something he’s using to make people feel bad about themselves. But it’s a real invitation to conversion, and you know, as Carolyn was saying and Archbishop Wenski was saying too, “Look at the ways that individuals can empower themselves to care for something that is beautiful and something that God gave us.”

I like to think of it as a real spiritual document that can be used by people who are secular, but in particular can be a way that all of us can be moved to a deeper conversion.

Wenski: Part of the Pope’s mission is to call us all to conversion. He does it in different ways and certainly Laudato Si’ is a clarion call to conversion, not only of individuals, but of nations, societies, of cultures.

“We need to get those relationships right with God, with our fellow man, and with nature if we’re going to have a happy and productive land to inhabit.” — Archbishop Thomas Wenski