Education as a Survival Strategy

Felix Odhiambo took his books everywhere. He read them as he walked to bathe. He thumbed through them as his friends played on the banks of the river. He pored over them until the last rays of light vanished. Studying was Felix's survival strategy. He was only 13 when complications from AIDS made his mother too weak to work. Left in charge of his 4-year-old twin siblings, Felix would leave school at recess and sell charcoal to feed the struggling family. Like many children in the village of Miranga in western Kenya, where 25% of the population is thought to have HIV, Felix was forced to grow up way before his time.

It was 2006 and access to antiretroviral therapy was not widespread. To contract HIV in rural Kenya meant likely death. Felix watched his mother, Patricia, fade. His father was in Nairobi, so the responsibility of caring for her and the twins fell on his adolescent shoulders. When Patricia became too weak to remain at home, Felix took her to the hospital, making friends with the night nurses so he could sit in their break room and continue to study his books late into the night. Studying was one way to deal with his grief. She died that August, and Felix had her buried next to their cornfields.

After her death, his father, Joseph, came home temporarily. Felix enrolled in school again and made headway in his studies. But a few months later, in April 2007, Joseph also began to show the signs of full-blown AIDS. Felix was once again missing school to feed his siblings and, eventually, dropped out. He found himself in the hospital, in the very same ward, befriending the very same night nurses so he could continue his studies. His uncle sold off a parcel of land to cover Joseph's medical bills, but Joseph died shortly before Felix was to take his high school entrance exams. Felix had him buried just outside their home; the twins were sent to live with relatives; and Felix was left to fend for himself.

No education without money

Primary school is free in Kenya, but a child who wants to advance farther needs to pay often prohibitively high fees to attend high school. All children must take a rigorous entrance exam to qualify for high school admission. Despite missing school extensively for 2 years in a row, Felix scored 391 out of 500 and graduated at the top of his class, which would normally garner him a spot in one of Kenya's better schools. But Felix lacked the money for fees and the means to get it. Children who have lost parents to complications of AIDS or other diseases also lose most of their possessions and large parcels of land, which are sold to cover medical and funeral expenses.

Undeterred, Felix reported to secondary school for classes. He was determined to attend the university. "I just went there," Felix says. "I was not in uniform. I had no books or anything to indicate that I was going for studies. After pleading with the principal, he told me that he cannot admit me unless I get somebody who was to pay my fee. So with my (score) of 391 on my certificate, I almost tore it into pieces. I was in tears. I was suicidal."

School fees covered

"I told her I was a total orphan and had no one to pay my school fees," Felix says. She asked him to produce his parents' death certificates and then asked what he would do with a sponsor. "If I had a sponsor, sky's the limit, what could I not do," Felix remembers saying. "When she told me my fees would be paid by TCB I saw a light at the end of the tunnel. My future was fully opened."

Later that week Felix was in school, thanks to the support of Madame Sarah and CRS.

"I went to the school with nothing—no books, no pens, no box to place my things—only the will to study," Felix says. He earned money to purchase shoe polish, soap and other small necessities by washing clothes for fellow schoolmates and selling them copies of his notes. On holidays he would weed people's farms. Felix kept his promise to Madame Sarah, graduating second in his class of 264 students. His name is painted on St. Paul's wall of fame as one of its top achievers.

"If I had not been a beneficiary of the project, my life would have been miserable," Felix says. "I had lost hope in my life. I had the grades but not the means to go to school. I would have had to opt to be a farmer but it would not have augured well with my life ambitions. That was the only alternative remaining in that I had the task of caring for my brothers."

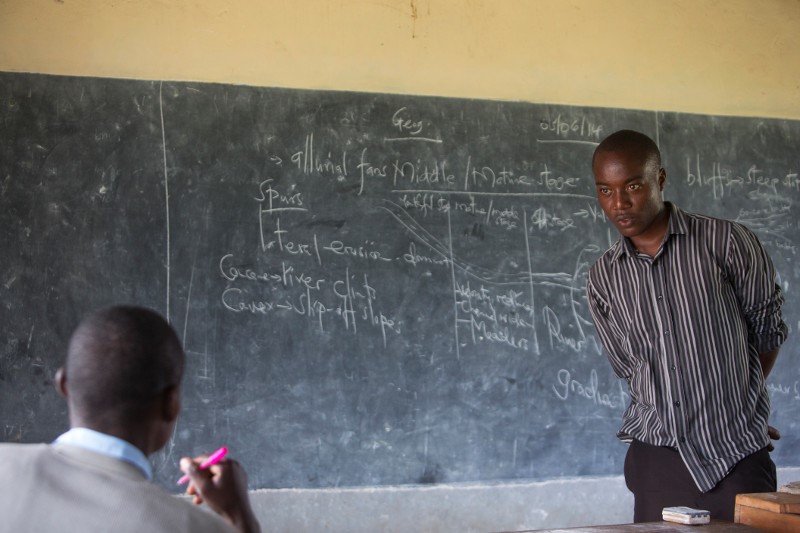

Determined student, teacher and mentor

"I don't joke when it comes to education," Felix says. "Each and every person must work hard. He (Levis) is capable of doing what I am doing. He must burn the midnight oil. Success does not come in a big way, it is accumulated by small efforts put together."